Many astronomers are no longer asking whether there is life elsewhere in the Universe.

The question on their minds is instead: when will we find it?

Many are optimistic of detecting life signs on a faraway world within our lifetimes – possibly in the next few years.

And one scientist, leading a mission to Jupiter, goes as far as saying it would be “surprising” if there was no life on one of the planet’s icy moons.

Nasa’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently detected tantalising hints at life on a planet outside our Solar System – and it has many more worlds in its sights.

Numerous missions that are either under way or about to begin mark a new space race for the biggest scientific discovery of all time.

“We live in an infinite Universe, with infinite stars and planets. And it’s been obvious to many of us that we can’t be the only intelligent life out there,” says Prof Catherine Heymans, Scotland’s Astronomer Royal.

“We now have the technology and the capability to answer the question of whether we are alone in the cosmos.”

The ‘Goldilocks zone’

Telescopes can now analyse the atmospheres of planets orbiting distant stars, looking for chemicals that – on Earth at least – can be produced only by living organisms.

The first flicker of such a discovery came earlier this month. The possible sign of a gas that, on Earth, is produced by simple marine organisms was detected in the atmosphere of a planet named K2-18b, which is 120 light years away.

The planet is in what astronomers call ”the Goldilocks zone’ – the right distance away from its star for the surface temperature to be neither too hot nor too cold, but just right for there to be liquid water, which is essential to support life.

The team expects to know in a year’s time whether the tantalising hints are confirmed or have gone away.

Prof Nikku Madhusudhan of the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University, who led the study, told me that if the hints are confirmed “it would radically change the way we think about the search for life”.

“If we find signs of life on the very first planet we study, it will raise the possibility that life is common in the Universe.”

He predicts that within five years there will be “a major transformation” in our understanding of life in the Universe.

If his team don’t find life signs on K2-18b, they have 10 more Goldilocks planets on their list to study – and possibly many more after that. Even finding nothing would “provide important insights into the possibility of life on such planets”, he says.

His project is just one of many that are under way or planned for the coming years searching for signs of life in the Universe. Some search on the planets in our Solar System – others look much further, into deep space.

As powerful as Nasa’s JWST is, it has its limits. Earth’s size and proximity to the Sun enable it to support life. But JWST wouldn’t be able to detect faraway planets as small as Earth (K2-18b is eight times bigger) or as close to their parent stars, because of the glare.

So, Nasa is planning the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), scheduled for the 2030s. Using what is effectively a high-tech sunshield, it minimises light from the star which a planet orbits. That means it will be able to spot and sample the atmospheres of planets similar to our own.

Also coming online later this decade is the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), which will be on the ground, looking up at the crystal-clear skies of the Chilean desert. It has the largest mirror of any instrument built, 39-metres in diameter, and so can see vastly more detail at planetary atmospheres than its predecessors.

All three of these atmosphere-analysing telescopes make use of a technique, used by chemists for hundreds of years, to discern the chemicals inside materials from the light they give off.

They are so incredibly powerful that they can do this from the tiny pin prick of light from the atmosphere of a planet orbiting a star, hundreds of light years away.

Searching close to home

While some look to distant planets, others are restricting their search to our own backyard, to the planets of our own Solar System.

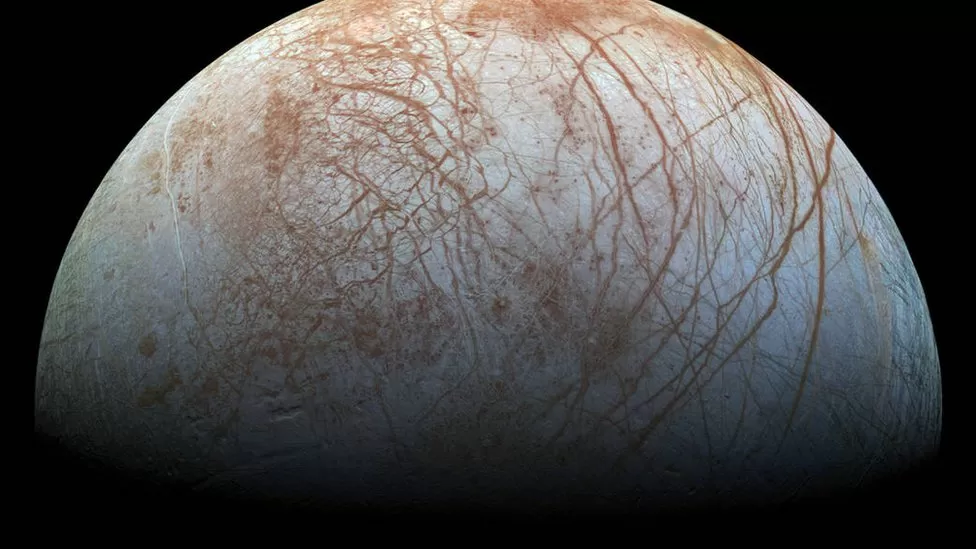

The most likely home for life is one of the icy moons of Jupiter, Europa. It is a beautiful world with cracks on its surface that look like tiger stripes. Europa has an ocean below its icy surface, from which plumes of water vapour spew out into space.

Nasa’s Clipper and the European Space Agency (ESA)’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) missions will both arrive there in the early 2030s.

Shortly after the Juice mission was approved in 2012, I asked Prof Michelle Dougherty, who is the lead scientist of the European mission, if she thought there was a chance of finding life. She replied: “It would be surprising if there wasn’t life on one of the icy moons of Jupiter.”

Nasa is also sending a spacecraft called Dragonfly to land on one of the moons of Saturn, Titan. It is an exotic world with lakes and clouds made from carbon-rich chemicals which give the planet an eerie orange haze. Along with water these chemicals are thought to be a necessary ingredient for life.

Mars is currently too inhospitable for living organisms, but astrobiologists believe that the planet was once lush, with a thick atmosphere and oceans and able to support life.

Nasa’s Perseverance rover is currently collecting samples from a crater thought once to have been an ancient river delta. A separate mission in the 2030s will bring those rocks to Earth to analyse them for potential microfossils of simple life forms that are now long gone.

Could aliens be trying to contact us?

Some scientists consider this question the realm of science fiction and a long shot, but the search for radio signals from alien worlds has gone on for decades, not least by the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence (Seti) institute.

All of space is a large place to look, so their searches have been random to date. But the ability of telescopes, such as JWST, to identify the most likely places for alien civilisations to exist means that Seti can focus its search.

That has injected fresh impetus, according to Dr Nathalie Cabrol, director of Seti’s Carl Sagan Center for the study of life in the Universe. The institute has modernised its telescope array and is now using instruments to look for communications from powerful laser pulses from distant planets.

As a highly qualified astrobiologist, Dr Cabrol understands why some scientists are sceptical of Seti’s search for a signal.

But chemical signatures from faraway atmospheres, interesting readings from moon flybys and even microfossils from Mars are all open to interpretation, Dr Cabrol argues.

Looking for a signal “might seem the most far-fetched of all the various approaches to find signs of life. But it would also be the most unambiguous and it could happen at any time”.

“Imagine we have a signal that we can actually understand,” says Dr Cabrol.

Thirty years ago, we had no evidence of planets orbiting other stars. Now more than 5,000 have been discovered, which astronomers and astrobiologists can study in unprecedented detail.

All the elements are in place for a discovery that will be more than just an incredible scientific breakthrough, according to Dr Subhajit Sarker of Cardiff University, who is a member of the team studying K2-18b.

“If we find signs of life, it will be a revolution in science and it is also going to be a massive change in the way humanity looks at itself and its place in the Universe.”